Stage Floors that Work

Stage flooring may seem like a dull topic, but many theatre consultants spend a lot of time on the subject. Frequently the stage floor needs to be sturdy enough for heavy scenery and large rolling loads, while also providing an appropriate degree of resilience for long-term performer health. It is a delicate balance that may be difficult to achieve.

Stages will often have multiple uses, and one of the most stringent cases is probably dance. Dancers are always at risk of injury due to the physical nature of their art. Performing on an improperly designed floor, without sufficient resilience or cushion, can lead to muscle fatigue and injury. It’s not just dance though: musical theatre, opera, acrobatics, and other activities with movement also deserve similar consideration for performer health.

A good resilient floor is not just for professional dancers. On the other hand, stage floors often carry heavy loads such as orchestra shell towers, personnel lifts, and sometimes an automobile. Many stage floors support scenery attached with screws. So how does a floor respond to a dancer en pointe, or the Sharks and Jets during the fight scene in West Side Story one night and a few nights later a symphony with a full-size (and frightfully heavy) orchestra enclosure?

A basketweave floor being preserved during demolition of adjacent areas. Note three layers of lumber below the plywood. Photo by author.

Many clients ask for things like a “sprung floor” or “basketweave” or even a “Marley” floor. Each of these specific terms may or may not be exactly what they want. Some companies or performers are well informed on the topic, while for others the requests may include buzzwords picked up over the years. What is clear, however, is they are looking for a floor that is safer for the athletic moves of dancers, regardless of whether it is traditional ballet, musical theatre dance, cultural, or other types of movement. Performers deserve to work on a floor that won’t hurt them.

Resilient flooring is best defined as a floor system that provides some level of cushion under foot. For our discussion, it is important to differentiate between the surface and the structure beneath. In the larger flooring industry, resilient floors often refer to vinyl or other similar products placed over a subfloor. For performance floors, the requirements for a resilient floor are different. The top surface might be wood and sometimes include a thin cushioning cover, meanwhile the structure below provides strength and often a response to impacts.

When someone asks for a particular floor, it is wise to press for more information to find out what is really desired. The request for “basketweave” may be code for resilience or liveliness. In other cases, users may ask for a “sprung floor” and not much else. If they ask for a “Marley” floor they probably don’t want a simple wood floor with only a vinyl top surface; the structure below also needs to react. Some discussion will be necessary to understand how each floor must perform. Tours of existing facilities may be the best approach to ensure the performers have the right system for their expected use, especially for discerning users.

Different theatre consultants use different designs, each tailored to the intended use and influenced by the user’s needs and budget. Some terms often discussed:

Marley: a name for a vinyl floor covering popular with dance companies, originally made by the Marley Company in the UK. That company is out of business, but the name carries on as a generic term. Generally, the surface is constructed of PVC, designed with a small amount of cushion and an appropriate level of friction for dance. There are several manufacturers of similar modern products designed to suit different dance types by varying the amount cushion and the coefficient of friction. Most are rolled out and fastened to the floor temporarily or semi-permanently. Vinyl floors alone, on a hard unforgiving floor, don’t provide adequate cushion for most types of movement.

A floor from an older dance studio that used springs to provide resiliency. Photo courtesy of Jason Prichard.

Sprung Floor: Any floor designed to compress and return to a neutral state. The springiness is within the floor structure and should cushion the landing of performers in all forms of movement. Back in the day, some designs used actual springs, while others relied upon the flexible nature of wood members or the compression of a resilient pad. Sprung floors may be anchored to a base slab, or they may be “floating” (not attached to base). Alternative versions of sprung floors have engineered layers of cushioning foam to create a particular level of resilience. Portable, modular sprung floor systems also exist and can be laid over harder surfaces to introduce needed resilience.

Basketweave floor: A sprung floor of traditional design using lumber laid flat in multiple layers, with each layer perpendicular and at mid-span to the layer below. The flexing of the wood members allows the floor to move under the weight of a performer. Variants using between three and five layers have been used. The number of layers, the type of wood, and thickness of the wood determine the liveliness of the floor. Modern versions may also incorporate resilient pads, but basketweave is as not common as it was decades ago.

It is certainly reasonable to make different floor choices for professional or community or educational spaces, but even young performers deserve some kind of resilient floor to avoid injury. Budget will be a strong influence, so there will be a value judgement regarding performance for the facility type.

A stage floor consisting of engineered sleepers, plywood subfloor, and Tempered Plyron. Note the layers are staggered to support the joints. Photo by Peter Scheu, ASTC.

Starting from the top (surface that is…), for a dance theatre where only one type of performance is expected, a permanent or semi-permanent top surface floor covering like a vinyl “Marley” surface may be appropriate. This type of floor must be cared for and can be damaged by heavy or rolling loads like personnel lifts. On the other hand, concert halls might prefer a beautiful hardwood floor, with structure influenced by the project’s acoustical consultant. For multipurpose theatres, dance may be just one component, so a permanent vinyl surface is an unlikely choice. For those spaces, where a week’s schedule could include lecture, then a concert, then a dance show, another solution is needed. Such a floor might be painted black or darkly stained, using a top layer floor panel such as tempered hardboard or Plyron, or perhaps tongue and groove hardwood. At one time the gold standard stage floor used edge grain (quarter sawn) heart pine, but that is quite difficult and certainly costly to obtain today. Recently there has been some development in composite or recycled floor panels which are black to the core, though some products may not meet the construction requirements in the International Building Code (IBC 410.2.1 – 2018). Oftentimes a floor that can be painted is preferred.

Below the top surface is a subfloor. That layer is structural, doing the work of carrying the load of occupants, equipment, and scenery. The composition of the subfloor and the support below determines the floor’s capacity. The International Building Code (IBC) requires a floor loading of 150 pounds per square foot minimum, but many stages will see higher concentrated loads and must be designed accordingly. Most subfloors are one or more layers of plywood, with the thickness of the plywood and the sleeper spacing determining the capacity.

The sleepers below the subfloor are an important part of the structure. The system may be “stick-built” with lumber such as 2×4, or use an engineered sleeper constructed of layers of plywood, a steel channel, and integrated resilient pad. There are some hybrid systems which use a cushioning layer throughout the space between subfloor and a concrete slab, with or without sleepers. For stick-built sleeper systems, resilient pads are attached to the underside of the sleeper. Many stage floors are laid over a concrete slab which must be level and dry enough to accept a wood floor so a vapor barrier may be needed to prevent the slab moisture from being absorbed by the floor. Some consultants will include insulation between sleepers to reduce the drumming sound of foot fall, and some may specify rosin paper or felt between wood layers.

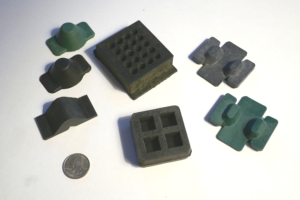

A collection of rubber or neoprene resilient pads from several manufacturers. The material hardness and shape contributes to the response of each pad. Photo by author.

The resilient pad in many modern floors is typically some form of rubber or neoprene. One might see durometer or “duro” ratings which don’t necessarily translate from type of one pad or cushion to another. Some pads simply compress, while others use special shapes that deform in a controlled manner as the load increases.

Floors used on most stages need to accommodate personnel lifts, scissor lifts, or in some cases forklifts. It is important to understand what type of load the stage will see and design the floor accordingly, especially where orchestra shells are planned. Commonly the floor design includes stopper blocks or other means to prevent over-compression of the resilience system. Without these stopper blocks, the tall towers of an orchestra shell may not remain plumb as the floor flexes underneath. It is never a good sight to see a shell tower wobble as it is moved across a stage floor; that problem is likely within the floor assembly.

Touring companies that incorporate dance or use other forms of movement may bring a “show deck” with them. The show deck might be decoratively painted and provide the resilience performers need, rather than depending upon each tour stop to have a well-designed stage floor. Sometimes show decks are prepared for show automation, with guide tracks and electrical connections built in for a particular tour. In other cases, the show floor may be only a series of panels (like hardboard) painted in the scene shop to save time. In the past, the show floor was a painted canvas stretched out and tacked at the edges.

Extra care is required where stage floors adjoin carpet, concrete slabs, or movable stage elements like traps or orchestra pit lifts. It is common to use blocking at these points to ensure the floor does not flex under load at the transition. Where heavy objects roll through loading entries, special floor transitions that are as flat and level as possible are needed The Case for Flush Saddles in Theatres by Bob Davis, ASTC- Spring 1999. Raised saddles are difficult to move pianos, road cases, and scenery across. Don’t be tempted to use a different flooring system in the wings; one consistent floor type from wall to wall of the stage is usually best.

Stage floors seem like a simple matter, but it should be apparent that is hardly the case. The equipment found on stages can be heavy and requires extra support. The health and safety of performers depends on the floor design, so getting it right is important. It takes care to design a stage floor that works and it is worth the effort.

By,

Paul Sanow, ASTC

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the American Society of Theatre Consultants. This article is for general information only and should not be substituted for specific advice from a Theatre Consultant, Code Consultant, or Design Professional, and may not be suitable for all situations nor in all locations.