Did You Know – Stage Dimensions

Theatre planners deliver net clear inside dimensions to a theatre owner. The payoff to the owner is not the exterior wall dimensions or the interior wall dimensions excluding ducts and cross braces, but the net clear dimension available for the Owner’s use, clear of everything.

Theatre at the Ace Hotel, Los Angeles. A view of an ornate auditorium connected to a backstage, ready for the next show. Photo by Christopher Harris

The plaster line is an important concept in this discussion. Imagine graph paper laid down on the stage floor marked with one-foot squares. The center line of the stage is the Y axis. The plaster line is the X axis, which is the same as “zero” on the Y axis. The “plaster line” is a horizontal datum defined by the venue as the starting point for the layout for scenic elements or stage rigging upstage or downstage of the proscenium opening. This is commonly the upstage side of the hard proscenium opening at the stage floor, or the rear of the fire curtain’s smoke pocket. The plaster line and center line are the lines from which all horizontal dimensions on stage are measured, both by the house and the show. One reason for this system of measurement is that a production can move into a new theatre and everything is still measured from the plaster line and center line, no matter how big the stage is or what shape it is. The absolute location of any point on any stage could be defined by two numbers, such as 4’ left of center and 6’ upstage of the plaster line or 12’ right of center and 2’-6” downstage of the plaster line. A touring production will have their own coordinate system and one of the first things the road carpenter and house technical director might do is to collaborate on the relative locations of the two plaster lines, the distance from house zero to show zero. Often the house has a brass dowel set flush in the stage floor at (0,0), the crossing of the plaster line and the center line, so it’s easy to find. It’s called the plaster line even though in most theatres it’s actually the line of the fire curtain smoke pocket, not plaster [though some venues measure from the line of the proscenium wall or the line where decorative “plaster” changes to backstage construction].

In planning a proscenium theatre, the net result of planning and construction yields these essential dimensions for the Owner’s benefit: (all are net, free of obstruction, so they are measured to the rigging lock rail, for example, not to the wall beyond)

- Proscenium width

- Proscenium height

- Onstage width left of center line

- Onstage width right of center line

- Depth from the plaster line to the upstage wall

- Depth from the plaster line to the last upstage set of lines

- High trim (the height of a standard rigging pipe batten above the stage floor when raised all the way up)

The Owner measures these dimensions in fractions of an inch. Consequently, when an upstage wall becomes thicker, say to accommodate more insulation or more wind resistance, the Owner expects that the additional wall thickness will be added on the OUTSIDE of the building, not deducted from the clear inside stage depth they programmed and have been promised.

One example to clarify the concept: For each Broadway theatre there exists a drawing that shows the stage wall outline at stage floor level. The drawing is crowded with dotted lines noted with elevations, each line indicating some obstruction above, like a stair landing at 17’ 6-3/4” AFF (above finish floor) here, a chilled water pipe at 27’ 0-7/8” AFF there, and so on, for every obstruction in the stage house. The scenery must be built to avoid these obstructions. The obstructions limit what can be accomplished on that stage. It’s far better if the planning and construction teams arrange for there to be no obstructions at all.

The equivalent concept would be planning a printing plant, where the reason the building is being built is to house a 200’ long printing press coming by boat, say, from The Netherlands. When eventually the press arrives, the building had better be big enough to clear the printing press. No column, sprinkler pipe, duct, roof drain or legal means of egress had better get in the way or the whole project fails. It’s not like most buildings, where a little bigger or smaller doesn’t really matter.

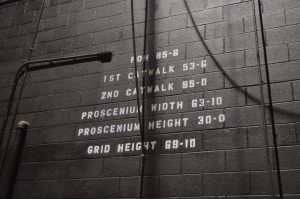

It is useful to include key measurements where house and road crews can see the information easily. Photo by Paul Sanow, ASTC

In most construction today the trades work on a “first come first served” approach to fitting mechanical and electrical trades into a space. Whoever gets there first completes their work and subsequent trades work in the space that is left. That “first come first served” approach does not work for stages, where the stage rigging is the last trade to arrive, is the least flexible trade, and the Owner’s scenery arrives after that. Where the elevation of a hung ceiling is given in the contract documents at least the trades know to stay above that elevation (or at least the smart contractors do). On a stage and in backstage corridors, with no hung ceiling, the trades “don’t get the concept” and their work creeps down into the Owner’s net space at the contractor’s convenience. Perhaps an “OWNER NET CLEAR” elevation should be added to the room title and room number block on the floor plan for each room. In Revit it should be possible to define a virtual object that represents the Owner’s net programed clear space, so any work that invades the Owner’s net space is flagged early.

Anecdote: On the original Pippin on Broadway, the scenic designer, Tony Walton, looking at the show deck during load-in, noticed the one-foot grid markers written on masking tape for use by the lighting assistants during focus. He liked them a lot, feeling they lent rhythm and ornament to his abstract comedic Charlemagne-era set. So, he painted, boldly, the focus grid on the show deck using gold paint. The assistant lighting designers all had to learn to read Roman Numerals.

By Robert Davis, FASTC

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the American Society of Theatre Consultants. This article is for general information only and should not be substituted for specific advice from a Theatre Consultant, Code Consultant, or Design Professional, and may not be suitable for all situations nor in all locations.