Technical Access in Performing Arts

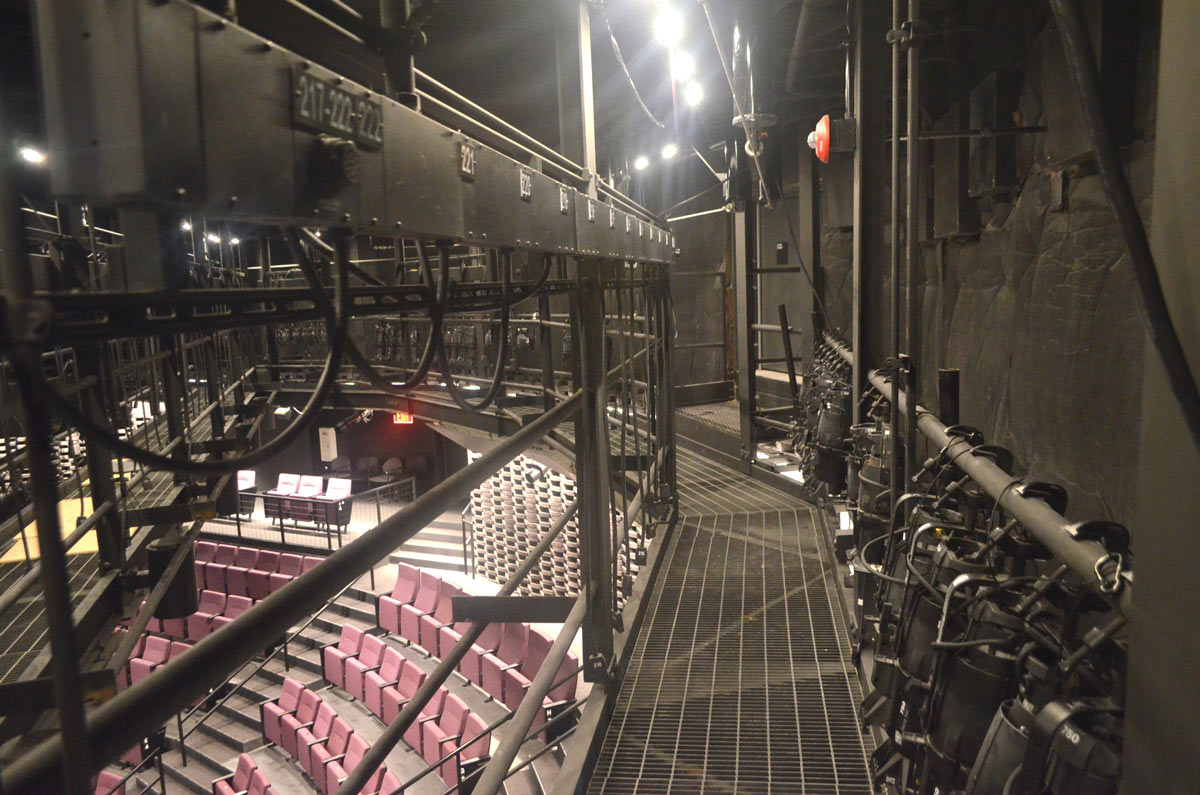

The fly space (loft) over a stage. This gridiron is 67-feet above the stage floor, and the rigging equipment is another 8-feet above the grid deck. This theatre is closed and preparing for renovation, so most draperies, lighting, and all scenery has been removed. Without a gridiron, how does one reach equipment so far above the stage? How tall a lift does one want to ride in? Photo by author.

All of this access is not inexpensive, but it is necessary. It is shortsighted to place equipment in places where it cannot be reached for adjustment, maintenance, or replacement. All too often, this access is not considered or may be “value engineered” out of the project. Ignoring access will have an adverse effect upon these buildings for decades, adding to ongoing operational costs at best, or becoming a safety risk in extreme cases.

The traditional design of a theatre usually includes a variety of special access areas for technicians. Examples are catwalks for lighting and access, fly floors, loading galleries, and gridirons. Some of these are found on both sides of the proscenium and are customized to each building based on specific production needs. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to these important features, even if each individual theatre consultant might have a preferred design recipe. Often, we must work with the design team to customize this access to work for specific instances. Let’s examine two specific cases and consider how changes in technology are changing attitudes; sometimes for the worse.

A self-climbing truss can be considered for spaces where catwalks are not possible or desirable. The hoist system rides in the truss and “climbs” the wire rope, allowing nearly all portions to be inspected easily. Moving lights, seen here, can be refocused remotely. Fixed focus lights are “bounce focused” by lowering the truss (usually more than once) and getting the light “close enough”. Photo courtesy of Steven Siegmund.

Catwalks with audience seating below. It is difficult to reach front lighting in a theatre over fixed seating on risers or a slope. Catwalks make this efficient, easy, and safe. Photo by author.

Rigging hoists installed in a room next to the fly tower. These hoists can be accessed and serviced with relative ease. This may be an extreme example, but servicing this kind of equipment high above a stage floor is difficult or impossible. Photo by author.

Now, back to those theatrical hoists or motorized rigging devices. Our industry has seen a lot of development in this area too. At one time, every motorized rigging hoist was more or less a custom design and commensurately expensive. Today, most rigging manufacturers offer motorized hoists, commonly in the form of “packaged” units, including zero-fleet technology. These are essentially mass-produced hoists designed to be compactly installed, potentially as a replacement for manual counterweight rigging. There are certainly benefits to these systems, and most theatre consultants will recommend motorized hoists as an option where it is appropriate (and within budget!). These hoists are not a silver bullet though, despite the marketing efforts of the manufacturers. For certain, the access needs are different and probably reduced from that required by counterweight rigging. No longer do we need a loading gallery with multiple tons of stored weight if there is no manual rigging. However, it is a mistake to mount a bunch of hoists 50 feet or more above a stage floor with no means of access, just because they can be operated from a button on the wall.

All theatrical rigging must be inspected and maintained on a regular basis. The industry is working hard to increase awareness because it is no secret there are rigging systems out there that are rarely looked at by qualified riggers. This poses a risk to people and property. The Entertainment Services Technology Association (ESTA) has developed ANSI standards for the inspection of all rigging systems, specifically in ANSI E1.47 Entertainment Technology—Recommended Guidelines for Entertainment Rigging System Inspections (enter/search, “ANSI E1.47” for the latest version.) The ASTC is a sponsor of ESTA’s Technical Standards Program. That standard requires a thorough inspection of hoists and related components annually. Even manual rigging needs regular inspection, though the requirements are slightly less stringent. Inspections for stage rigging require access to each and every component of the system. A gridiron usually allows this kind of access, but a hoist mounted to roof structure with no way to stand next to it will not. All too often it is assumed a personnel lift will allow access to all of the components, but there are limits to the size and types of lifts that may allow such access. A tall scissor lift or boom lift can be a challenge backstage. Consider trying to reach a machine or a loft block 50 feet above a stage, trying to thread the lift basket through a sea of battens, wire rope lift lines, cables, and hanging scenery to solve a problem. Can the appropriate lift even be delivered to the stage? Is it too heavy for the stage flooring system? A proper gridiron and/or a catwalk to access the machine can resolve this issue safely.

Reaching lights and rigging equipment are just two of the most common operational access problems created by lack of understanding or forced by limited budgets. Just because the stage is in a high school does not necessarily reduce the need for access. Much like designers should consider how to service or replace mechanical equipment, the same goes for theatre equipment. There can be creative solutions to many challenges in theatre design, but until we can send out technicians with reliable wings or jet packs, we must offer a way to safely access all the equipment in these spaces, and sometimes in a hurry. Lighting and rigging are just two categories of equipment that need access. We still want the show to go on, safely.

By Paul Sanow, ASTC

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the American Society of Theatre Consultants. This article is for general information only and should not be substituted for specific advice from a Theatre Consultant, Code Consultant, or Design Professional, and may not be suitable for all situations nor in all locations.