The Case for Boxes

By Robert Long, FASTC and Robert Shook, FASTC

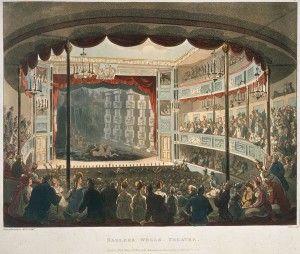

Image of a production at Sadler Wells Theatre, London circa 1808 (Image courtesy of Wikipedia – public domain)

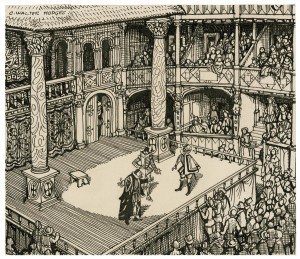

Box seating has been a part of the architectural vocabulary of auditorium design since the art forms of theatre, music, opera and dance began to gain prominence in the late 1500s. Boxes evolved in Europe from the use of found spaces that included salons, tennis courts, bear-baiting arenas and interior courtyards, and in Asian countries with the use of teahouses and festival platforms for performance. Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre is an early example of the intentional use of box seating in auditorium design. Today we ask ourselves, why DO we continue to include box seating in the design of modern auditoriums?

Boxes cost more per seat than seating on the orchestra floor or in a balcony. Side boxes often require additional access and exit corridors, and accessible circulation paths to connect to nearby audience public elevators. However, the value of side boxes cannot be measured only in terms of cost, but in terms of functional and artistic advantages.

Boxes can be very useful architectural devices indeed. They can be used to create strong visual connections between elevated seating areas – mezzanines, balconies, and circles – and the stage, thus increasing the sense of intimacy and deeper emotion for all patrons. They also allow otherwise-empty side wall areas to be animated with audience, no small consideration today, where theatre managers are keen to amplify the “live” experience of theatre-going. Unlike the increasing popularity of “stadium seating” in movie cinema design which creates a strong, unobstructed, one-on-one experience between the audience member and the large projection screen or video wall, auditoriums designed for live performance strive to enhance connectivity and the communal experience.

A side box can serve other purposes, as well. Box seating can be used to provide ADA-required seating opportunities for audience members in wheelchairs or with other special seating requirements. Acoustically, the side boxes provide advantages for bringing natural sound more effectively back to the main seating areas by reflecting sound energy off the undersides and fronts of the boxes. Side boxes provide opportunities for antiphonal music, as a location for temporary lighting and sound equipment, and occasionally for camera positions.

The imagined view of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, Act 1, Sc 3, as performed in an Elizabethan Theatre. (C. Walter Hodges)

The inclusion of side boxes in modern theatres is often driven by financial mandates. Some institutions find it necessary to recognize the generosity of benefactors with an elevated experience, which often includes special seating and access to a VIP lounge. These theatres often include the installation of special boxes similar in concept to “corporate” boxes in sports stadiums, with amenities such as private ante-rooms with food and beverage service. Box seating may also provide increased comfort in the way of extra legroom and wider seats – not unlike airlines’ offerings – for premium pricing or recognition.

One can argue that boxes and side galleries compromise the viewing experiences for their occupants. For one thing, they usually require viewers to rotate their heads and bodies in order to view the stage; or they require non-fixed seats that rotate. In many theatres, audience members seated in boxes might actually lean onto the balcony railing in order to improve their view. Finally, box occupants nearest to the stage find themselves with restricted sight lines to the rear areas of the stage.

Image of the Historic Asolo Theater, originally constructed in Asolo, Italy in 1798 and the decorative elements were moved to Sarasota spaces not once but twice. Restored in 2006, since this photo. A new definition of box seating. (Photo by David Greenberg)

For the most part, however, these challenges are discounted by some patrons who consider side gallery and box seating to provide a more exclusive experience, who value the closer proximity to the performers, or who appreciate the see-and-be-seen aspect. Side galleries and boxes generally work best for headliners, music, and arguably, opera. They are less advantageous for dance and cinema presentations.

While box seating has remained an important aspect of auditorium design for the last five centuries, the evolution has been interrupted by two cultural events, both of which were momentary in the ongoing continuum. In the 1920s, many conventional theatres had their boxes shaved off when motion picture became a driving force and enlisted existing theatres for film presentation. The second case was the arrival of “mid-century modernism” in the 1950s which eschewed the use of ornamental architecture. The side box regained its place in auditorium design again in the 1970s and continues to be used robustly today.

Live performance in our modern culture is still based on nurturing cultural traditions and respecting the individual performers and their art forms. Are seating boxes simply a remnant of historical practice, or do they actually retain their value with modern audiences for whom intimacy and immediacy are prized above all else? The next time you attend an event in a theatre or concert hall with side boxes, imagine what the room would lose if these boxes did not exist. The answer may help you to form your own opinion of the value of these boxes.