Open Stage Design & James Hull Miller, ASTC Founding Member

The concept of Open Stage Design encompasses two distinct ideas. First, the audience shares the same space as the performers – there is no wall separating the performers from the audience. Second, the audience envelops the performance area, either partially or, in some instances, completely.

The “open” stage design has its roots in the beginnings of the Western Tradition of theatre. Historians tell us the first stages were the threshing floors of the area around the Mediterranean Sea. After the day’s work had been completed, the workers and their families would entertain themselves with skits and dramas performed on the hard, open threshing area, with the spectators standing or sitting around the periphery.

The “threshing floor stage” was adopted into the classic Greek (Epidaurus, for example) and Roman theatres that later developed. Even when the Romans began to place a roof over their theatres, the stage and audience were both located in the same space.

In the 16th century, the courtyard style began to evolve in Spain and England. The inns of the day usually had a courtyard where the animals used by traveling guests were kept. For theatre performances, stage platforms were constructed on one end of the courtyard and the audience stood around the stage and on two or three levels of galleries around the periphery of the courtyard. When dedicated theatres, such as Shakespeare’s Globe were built, they followed the same circular plan.

In the 18th century, developments in artificial lighting allowed theatre performances to move completely indoors and encouraged the proscenium theatre design. Here the stage was viewed through a “window” in a wall creating the proscenium opening. The audience was in one space and the performers and stage machinery that was used for scenic effects was in a separate space on the other side of the wall. From the beginnings of the 18th century to the middle of the twentieth century the predominate theatre form was the proscenium theatre with the performance area separated from the audience.

In the United States and other Western countries, two synergistic theatre movements began in the late 1930s. These were the Regional Theatre Movement and the Open Stage Movement, influenced by dramatic realism and the “Little Theatre” movement. The Regional movement had the goal of distributing theatre activity out of the main large cities into the smaller cities. Thus were the beginnings of organizations such as Arena Stage in Washington, DC and Pasadena Playhouse in California. The people leading the regional movement wanted performances to be more interactive with the audience and they also had restricted budgets. It is not surprising these two conditions favored returning to the earliest foundations of drama. The “open” stage theatre form was the right fit for the regional movement, but the Open Stage Movement became a driver of alternative theatre design outside of the regional movement.

One of the founding members of the American Society of Theatre Consultants (ASTC) was James Hull Miller. His is an example of the right person being in the right time. He began his career at Princeton University in the late 1930s. While a student, he was part of an organization that provided labor to move things, including theatre sets for touring shows. The sets usually arrived by train and had to be moved to the McCarter Theatre on campus. This was his introduction to the theatre world.

Inspecting a projector, (L to R): R. Duane Wilson, ASTC (author), Robert Heyser (Wilson’s associate) and James Hull Miller.

Mr. Miller graduated from Princeton in 1939 with a BA in English Literature and an interest in theatre. Miller described to this author an experience which directed his career in theatre. While walking down Nassau Street in downtown Princeton across from the university, he was looking at the shop window displays and came to the realization that a simple object could effectively suggest a scene. A model of the Eiffel Tower meant Paris, a double deck bus or Big Ben’s tower suggested London. This could be applied to stages and simplify the complex theatre scenery he was seeing used at the McCarter. He became fascinated with the potential for open forms of staging in contrast to the traditional proscenium model.

Between graduation and the start of WWII, Mr. Miller worked for a year as business manager at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago and as a Technical Director and Lighting Designer. During the war he served in the Army, 24th Armored Division from 1941 to 1945

After the war, he taught Theatre at the University of New Mexico from 1946 to 1955. Miller then moved to Centenary College in Shreveport, LA in 1955.

Mr. Miller became heavily involved with the open stage movement in the mid 1950’s, consulting on the design of several theatres. In 1958, he gave up full time teaching and opened his Arts Lab Studio dedicated to theatre consulting and development of self-supporting scenery. Jimmy Miller thus became one of the earliest American theatre consultants.

The book, From Art to Theatre: Form and Convention in the Renaissance (University of Chicago Press, 1944), by George R. Kernodle was cited by Mr. Miller as an influence in his philosophy of open stage design. Kernodle and Miller likely interacted in the mid-1950’s during the time Kernodle was at the University of Arkansas and Miller was in Shreveport. Miller also worked with proponents of open staging, most notably Art Cole, and was influenced by them.

James Hull Miller was a pioneer in theatre consulting, starting his practice without a side job such as that of a full-time university faculty member, scenic designer, or other source of income. In his practice he formed a mutually beneficial relationship with Al Koga at Hub Electric. Hub published and sold his written works through their Bulletins and provided lighting equipment for many of Miller’s projects. Mr. Miller promoted his consulting practice through written pamphlets detailing the advantages of open stages and self-supporting scenery. His writings were some of the first by a modern theatre consultant to describe the various forms of theatre stages, the importance of acoustics, sight lines, and lighting in contemporary use. Russell Johnson of ARTEC was a longtime friend and mentor on acoustics.

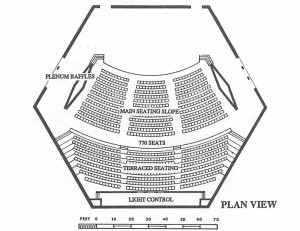

Plan of a typical Miller-designed theatre. Excerpted from An Architectural and Engineering Proposal for Open Stage Theatrical by Al Koga (provided by author)

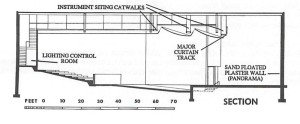

The typical Miller-designed theatre featured an audience chamber seating 300 to 500 with appropriate volume, wall surface shapes, and ceiling cloud reflectors to ensure good acoustics for the spoken word. The seating was steeply raked, offering “every row” vision of the stage. The stages were wide, as deep as possible, and had a plaster “Panorama” wall at the rear for projection. Lighting catwalks were located for maximum effectiveness above the stage and audience. Typically, there was a front curtain, and a midstage and upstage traveler. The travelers were used to mask the projection wall and wings, along with caliper walls downstage that provided side masking and multiple side entrances to the stage, and apron or thrust.

Miller advocated open staging and self-supporting scenery as a means of reducing ongoing production costs for small school and community theatres well before the publishing of the William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen’s landmark book, “On the Performing Arts: The Anatomy of their Economic Problems,” (Westview Press, 1965). Many, if not most, of Miller’s projects resulted from his philosophy that small theatres could be built and operated far less expensively than traditional proscenium theatres.

Section of a typical Miller-designed theatre. Excerpted from An Architectural and Engineering Proposal for Open Stage Theatrical by Al Koga (provided by author)

He was not only concerned with the design of the theatre building, but also how to use the space effectively. Miller devoted much time and effort to new methods of constructing theatre scenery. In place of the traditional scenic flat, he developed means of constructing light weight wood frames that were strong and smooth on both sides, i.e. requiring no corner blocks and keystone blocks. This resulted in flats that could be joined by fabric hinges, similar to the folding screens of Far East Asia, with two useful sides and folding compactly for storage or transport. Other framing techniques allowed flats to be easily clamped together to form three-dimensional, stable free-standing set structures. By reducing the scenery to self-supporting elements and folding screens, Miller showed that theatre companies and small schools could tour productions with sets that would fit in the baggage hold of a standard bus, thus eliminating the “truck” from the typical “bus and truck” show.

Miller, as part of his consulting scope on a theatre project, would typically spend a week between the Certificate of Occupancy and the opening production. He worked with the users in the theatre’s scene shop to build scenic elements and folding screens using the methods he developed. He also taught lighting techniques, lensless projection, and other stagecraft that was useful in open stage production work.

There’s much to be learned from James Hull Miller’s practice. Today, perhaps not everyone would appreciate the Open Stage form, nor is it appropriate for all facilities. But this concept continues to be an option for small organizations operating on tight budgets. As Miller demonstrated, we are constantly adapting the designs for new theatres, even reaching back to the open stages of the Greeks for inspiration.

Mr. Miller retired from active Consulting in 1985 and died in 2007.

By R. Duane Wilson, ASTC

——————————————————-

Publications:

Stagecraft for Christmas and Easter Plays

Self-Supporting Scenery for Children’s Theatre and Grown-Ups Too, a Scenic Workbook for the Open Stage

Small Stage Sets on Tour

Stage Lighting in the Boondocks

Above are still in print and readily available

No longer in print, but usually available on Amazon

Designing Small Theatres

Technical Aspects of Staging in the Church

James Hull Miller wrote several Bulletins published by Hub Electric Company of Chicago. Some of these can be found online through the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) sponsored by the US Department of Education. https://eric.ed.gov/

Notably Bulletin 109 The Open Stage, which is a comprehensive introduction to the James Hull Miller philosophy.

——————————————————-

Buildings:

Marjorie Lyons Little Theatre. Shreveport, LA

Midland Community Theatre, Midland TX

Herschel Zohn Theatre, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM

Theatre of Western Springs, Western Springs, IL

Barat College, Lake Forest, IL

Mr. Miller consulted on several dozen high schools and small colleges across the mid-West in small communities where the school auditorium served as the community multipurpose venue.

Compiling a list of Miller designed spaces has proven difficult as current users often do not know the origins of the space they work in. If readers know of additional theatres where James Hull Miller was part of the design team, I would be interested in hearing from you. Please email the author,