How Much? The Grossly Larger Space

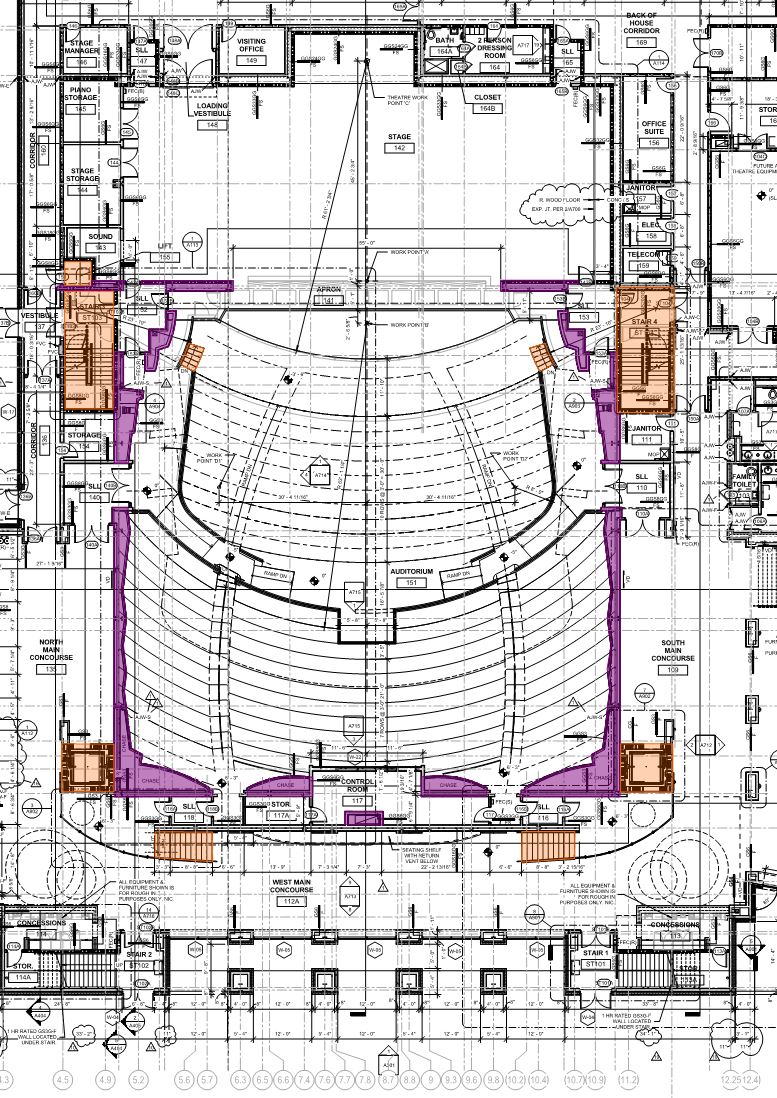

First Floor Plan of a 2,500-seat performing arts theatre. Violet areas are thickened walls and chases, orange areas are vertical circulation. Floor Plan of Columbia County Performing Arts Center, Evans, GA courtesy of Craig Gaulden Davis Architecture.

As an example, in a simple clear span garage or shed, the difference between the Gross and Net area is the area occupied by the perimeter walls. For a 25 foot by 25-foot garage the Gross area is 625 square feet. If the walls are 6 inches thick, they occupy an area of 49 square feet. So, the resulting Net area is 576 square feet and the Gross to Net is 1.08. This is an extremely low Gross to Net ratio; of course, most buildings are not nearly this efficient.

In the real world, there are many areas of a building that the owner/developer cannot lease to users. These include utility rooms for the electrical service, fire sprinklers, telephone and IT services, trash room, loading docks, HVAC equipment, and circulation space. The circulation areas include stairways, elevator shafts, hallways, lobbies, rest rooms, and similar common areas users need to reach program areas. The owner/developer must pay to build all this “extra” space but cannot make money from those areas. Therefore, there is a powerful incentive to keep the Gross to Net ratio as low as possible.

Because of the competitive market and the price sensitivity of the buyer, residential construction has become a leader in lowering the Gross to Net ratio. Use of roof mounted HVAC or split modular heat pumps has eliminated the furnace room. Tankless water heaters and other innovations have reduced the areas of a home needed for utility devices to a minimum. In a modern home, virtually only the walls subtract from the Gross to Net.

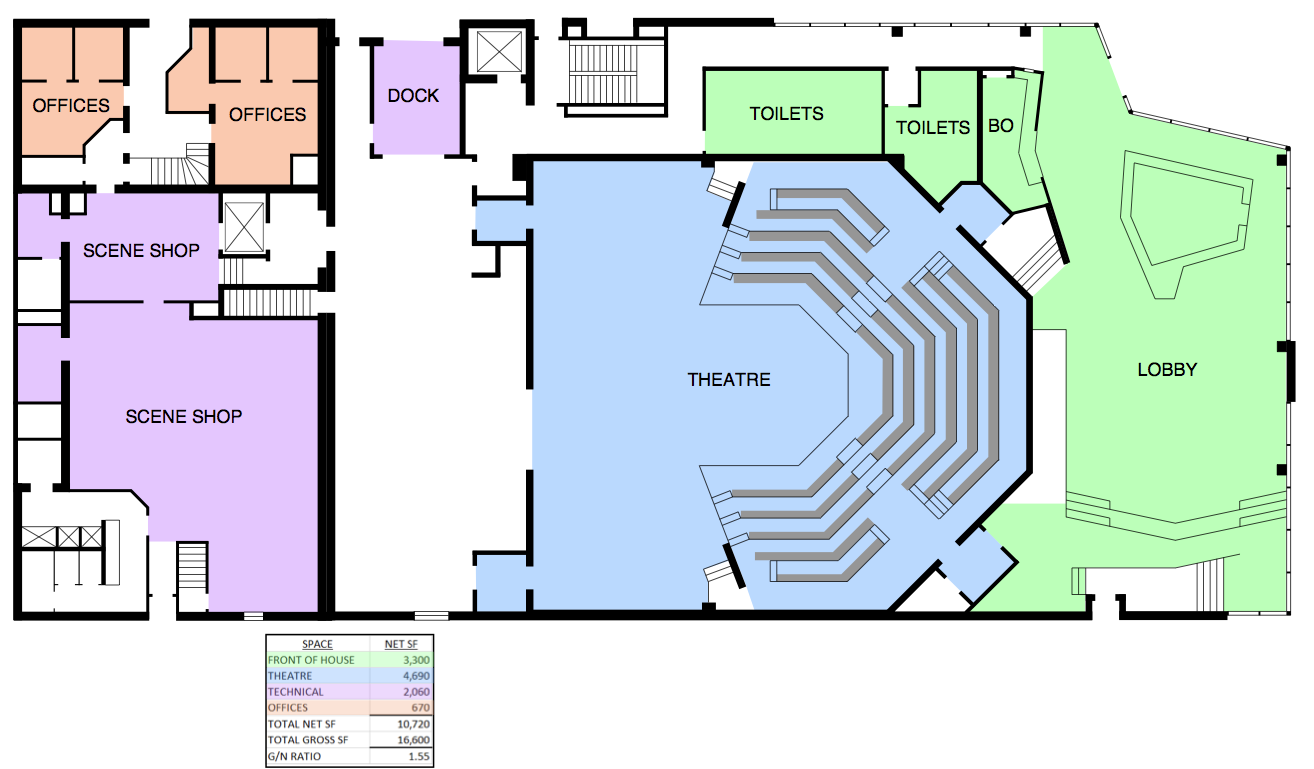

Readers of the previous installments in this series should not be surprised that a building for the performing arts has a high Gross to Net ratio. The factor commonly ranges from 1.6 to 2. Many theatre consultants include key areas such as lobbies, front of house restrooms, and storage areas into net space calculations because of their unique importance in performing arts. So, where other building types might consider those as part of the gross, in performing arts it is critical to reserve space for those functions early in planning. The following is a discussion of some of the reasons why the ratio is so much higher than the typical building.

Large duct to move air slowly and quietly at attic level above a concert hall. Photo by Michael Parrella, ASTC

Another driver of greater Gross to Net ratios in performing arts are the walls of the theatre or auditorium. The outer walls of the auditorium provide sound isolation keeping outside noise away from the performance space and are key to fire separation. Acoustics and room design control the shape and location of the inner auditorium walls. In many theatres it is possible for the distance between auditorium inner wall and the outer wall to be 3 feet or more. Some of this space can be used for sound and light locks, ducts, and for some stage lighting positions. Walls providing acoustic isolation and special shaping may seem like wasted space, but that perceived waste is doing critical work.

Code requirements for the size of restrooms and the number of fixtures assume the building users visit the restrooms continuously and at random times. If the standard code requirements are applied to performing arts venues, we see familiar long lines at restrooms, especially for women. This has become unacceptable and there are recommendations for increasing the number of restrooms and fixtures. [Please see: "When You Gotta Go…!, A Serious Discussion About Toilets" ] To prevent lines, larger restrooms with more fixtures are needed and must be planned in advance. In one example known to the author, the restrooms cover about the same area as the large lobby. For that 2,200-seat hall, there are 99 women’s stalls and 60 fixtures for men: a huge investment in both area and plumbing (but few lines at intermission). A common rule of thumb is a ratio of 1 fixture for approximately every 25 seats, with 2/3 dedicated to women. Today we are also planning separate, non-gender specific or family restrooms which add to the space required.

Performing arts venues require unusual spaces, not normally found in other buildings. These are part of the net usable area calculation but are used in a variety of ways which must be considered even if they are not all revenue-generating. These spaces may include a first aid station for patrons or staff, security offices for both front of house and backstage, rooms for lighting control, light storage, and separate rooms for audio equipment. Often there is a need for a VIP lounge for special patrons, and catering support with separate facilities for traveling shows, both front of house and backstage. Dressing rooms for performers and support spaces for scenery, costumes, props, musical instruments, and piano storage, etc., need to be accommodated as well. The list of support spaces for performing arts goes on and on, impacted by the specific needs of the organization. All are important features, but they add up quickly and affect the bottom line.

Circulation is another category that consumes a lot of space. Performing arts venues typically have several areas for audience seating, like the main floor, balcony, loge, tiers, boxes, etc. Each requires access for the patrons to move, often on separate paths due to the variety of levels. Accessible routes for wheelchairs are needed, often to many areas of seating, so ramps and elevators enter the mix of requirements. These all add to the building footprint. It is not unusual for ADA access requirements to significantly increase the circulation area in a theatre compared to venues designed before the 1980s.

Mechanical systems, thickened walls for isolation and shaping, audience circulation, and atypical spaces are the primary categories that grow the Gross footprint while not contributing to the Net usable area.

We’ve not even touched on the equally demanding requirements for circulation paths for actors, musicians, technical staff, scenery, etc. Now, in 2020, we are expecting to increase space for social distancing, audience screening, greater circulation areas, and larger volume for robust mechanical systems. It may seem like performing arts buildings are inefficient on the surface. Nonetheless, all these contributing features are important to the function of a well-designed performing arts venue.

By R. Duane Wilson, FASTC

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the American Society of Theatre Consultants. This article is for general information only and should not be substituted for specific advice from a Theatre Consultant, Code Consultant, or Design Professional, and may not be suitable for all situations nor in all locations.

Additional Information

ASTC members are particularly interested in this topic. There are several articles providing additional insight, found below.

Tips for Front of House Planning, by Robert Long, FASTC, July 2017

Tips for Back of House Planning, ASTC members, December 2016

How Far is Too Far, by Robert Shook, FASTC, September 2015

How Far is Too Far, by Robert Shook, FASTC, Spring 1996

The Multiplier is Truly Gross, by Robert Long, FASTC, Fall 2005

A Quick Peek into Dressing Rooms, by Lawrence Graham, ASTC, Fall 2002